Rev. George Kornegay

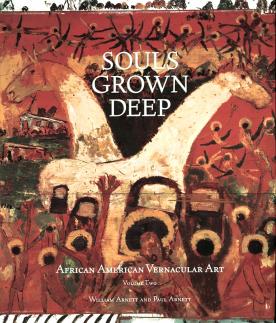

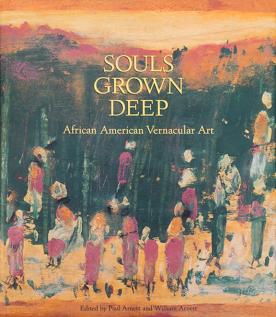

About

I was born on November 23, 1913, in Bibb County, Alabama. My daddy farmed and worked at the O.C. Grimes Veneer Company. He worked the Number Nine mine in West Blockton, digging coal. He also worked at the mill where they made barrels. My mother stayed home and take care of the kids—six boys and four girls. I was the second child, George Paul Kornegay.

I farmed. I went to school, Alabama Mission School, about four miles from here, in Brent It was run by northern people. The president, John Baker, a minister from Washington, was a white man, but the students and all the teachers were black. The northern states sent lots of clothes for the children, and furnished our books and stuff, and sent money. It run from the first to the tenth grade.

I did real good at school, but I had to stop school and help my daddy sharecrop. We had bought a young mule for a dollar and a half so we could be independent. We didn’t want no white man taking it all. Back then they give you that mess about “One more bale and you’d-a made a profit.”

The land we’s on was bought by my daddy, twenty-eight acres of land and a two-story house, for a flat hundred dollars, sold to my daddy by Charles Hogan. (He was a Indian, a Cherokee Indian tall, had long pretty hair.) Charles Hogan didn’t have no more relatives here. Ann Hester Hogan, his wife, had died—I had ate a heap of her bread—so Charles Hogan moved to Indianapolis, Indiana. That’s the last time I heard from him—1925.

We lived right up there on the hill. We been in this place a longtime. I mostly was raised right up there where those pine trees are at, them big trees. I got lots of white-people friends around here because I done a heap of work for them. I worked the land for them, set out their flowers, and decorated their yards, trim their hedges. Worked hard for them. Hoed and pinched their cotton. From a plow to a preacher, from a preacher to a steel mill, from a steel mill to a veneer mill. Double shifts I worked. And a cotton sack, and a plow, and a saw mill, and a paper mill, and all that stuff: had to make a living for my people.

I worked up in Tuscaloosa. It’s thirty-five miles from here, but all my kids was at home. Fourteen of us living at home. And I wasn’t making enough money to support them. I say, "Well, Lord, I got to move somewhere, got to get up and move." So he showed me. He say, "Get up Monday morning, and get your shoes, and carry some extra clothes, and go to Century Foundry," so I got up and went with my cousin.

I got up there around 12:30, and there was so many people standing around the employment office. I said, “Lord, what did I come here for?” So my mind say, Get out about ten foot away from the crowd, away from everybody.

So one of the proprietors was working the personnel office. So he kept looking at me and I kept looking at him, you know. He look at me, I look at him. He come just as straight to me as he could come. He say, “Do you ever work here before?”

I say, “I was working at the shell plant during the wartime when they need all them bombshells.”

He say, “What was your number?”

I say, “863.”

He say, “Follow me,” and I followed him on down to personnel, and he told me to get a temporary—get me a badge—and told me to get down to Number Six and go to work. And I went on down there. Got me a place to stay. Next morning they writ me up. It wasn’t a single soul hired in two months in that plant—nobody but me. Folks say, “Man, you lucky.” I say, “No, I ain’t lucky. This is the plan of the Almighty God.” And, you know, I stayed there until I got ready to go, and never missed a shift. And for sixteen hours. Lay down on a bench about a couple of hours, get back up, cut about another eight hours. My children laying down asleep and I’m trying to make a living for them, that’s what I did.

And so I told my wife sometime, "I got a right to hurt." I say, "I done a whole lot of hard work." But I raised up my children and I enjoyed it. Some of them help me, some won’t, but they all mine, and I don’t think no more of one than I do the others. I don’t make no difference between my kids; sometimes it make a division in the family when you think more of one than the other, no matter if you got two or three special ones in there. I say, "Listen, if I ain’t got enough money to buy all y’all a pair of shoes or buy all y’all some clothes, all y’all go barefoot and half-naked until I get in shape to do it for every least one of you." And so God fix it that when I got ready to buy them clothes and shoes, I could go right around the bases. And they loved me for that I don’t have no difference—they all mine, whether he good or whether he bad, and I respect him, because that’s what he is. They tell me, "You taught us better, you carried us to church, made us go, went with us. You taught us the right thing." Say, "If we go sour, that’s our business, but you done your best to raise us up." And they still love me for it.

So I have a nice family. Me and my wife, we been married since 1934. We come up together as kids, got married at sixteen, seven-teen just children. I’m a father of twelve—eight boys and four girls. Three of my children are dead; I still have nine. I figure God has been good to me, let me stay here this many years, you know, to live to see my children grown.

I’m a minister. Been a minister fifty-seven years. I’ll be eighty-four years old, still pastoring. I love my congregation, I love people, and I love God. And I try to treat everybody right. So this is my religion, this is my path.

I’m African Methodist Episcopal—A.M.E. Zion. I’m senior pastor in the conference now. They call me "Big Daddy" in the church. I been at this spot thirty-two years. We are Methodist, you know, and Methodist preachers ain’t supposed to stay in one place but four years. Then they have to move, move around. I was transferred in 1965 from Montgomery back to Cahaba, and I haven’t moved since.

I baptized thirteen back here in August. Had them in the creek, the old-fashioned way to baptize them. And I enjoyed baptizing them in that water. You know, that’s the way we used to do it way years ago: baptize them in running water.

I had wanted to be a doctor, you know, but it wasn’t my calling. My calling was in the ministry. I got a divine calling. I run from it at first. I think I was afraid of it, but God, he stayed at me. I ask him to give me these signs if this is what he mean for me. And he sent them. And the end of it come from a choir of angels come to visit my house. Come from the east into the house, go down the hall, go around my bedroom. And then leave to the west.

This property is a sacred place. This was a Indian village way back before my daddy got out here. It’s a burial place. My daughter at certain times can hear voices out here talking but she can’t tell us what they’re talking about. This is one of them places where you can come when you’re feeling bad and go away lifted up. They all say this is a sacred place.

It is enough stuff in this ground around here to run Bibb County and Montgomery. I’m sitting on—my house is sitting on—one of the richest spots it is in Alabama. Now that’s a secret I don’t tell, but my house is sitting on it, and every once in a while I get signals. Sometimes I be up at night reading, you know, something will follow me down to my bedroom. And I look around, see if I can see anything. And next day when I get up, something be following me in the house. And I get the signal—to let me know what’s here.

Way years ago something had told me it was something important here, but I never did exactly get the message, never did get the understanding, and it told me what to do, how to do. And then I couldn’t sleep, and every time I’d wake up, the same thing would be worrying me: that something big is here. People say, “Why don’t you do something about it?”

I say, “Probably it ain’t my time. Some of my kids may hit the jackpot here, not me.”

Well, I kind of had this place checked out, and eventually those things, those signals, left, but they come back to me again. The voice say, “They say it wasn’t nothing here, but, see, I say it is here. Nobody, nobody going to inherit but you.” And it ain’t worried me no more.

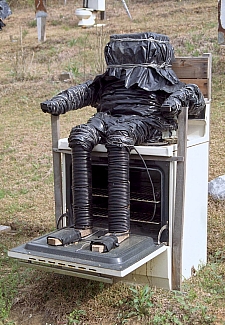

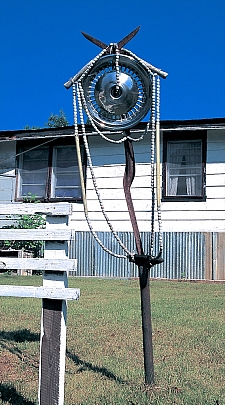

I started on this yard when I retired. When I was sixty-six years old, about 1980, I retired, laid it all down. I had started a few things in the yard before that. When I retired for good, I stayed at this every day.

The rock right there—this is where I put the first piece down. The red rock. When I put this in here I was intending to sculpture a face on that rock. Now, the mind said, Don’t sculpture a fact upon it. Say, Upon this rock I’ll build my church the gates of hell shall not prevail against it. I’ll give you the key to the kingdom but what you find on earth shall he found in heaven, what you loosen on earth shall he loose in heaven, and this was my beginning. I love this because this is the beginning, and all of this is going to have an end.

I guess I told the story more than one time: When I put this out here, I didn’t put it to say I’m going to get rich or going out to make me some money, but I put it here because my mind say to put that rock right up there. Little old red rock: That’s where I started. And then I kept ‘spanding, I kept ‘spanding, I kept ‘spanding.

At first I had said, “Well, I’m going to do this thing here and then I’m going to quit.”

God say, “Go further.”

Overnight, when I lay down, I say, “Tell me how when I get up in the morning.”

He say, next morning, “Put a piece here, put a piece there, put a piece over yonder. Go back and get that; never throw nothing away.” So I fixed it up his way. I spaced it, you know, with the eye God give me. Everything got a place. I told them, “I can see more with my eyes closed than they can see with their eyes open.”So God gave it to me, and I’m going to use it till I die.

I walk this place every day. I do something constantly every day. I enjoy my work. Some of them say, “Well, Rev, what you going to do now?”

I say, “I don’t think this stuff is all that important.”

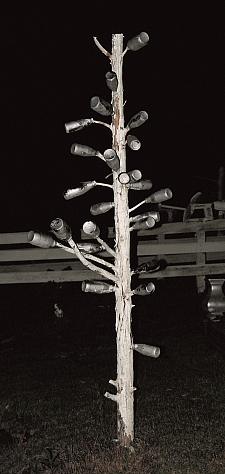

But I say if I don’t do nothing but take my post-hole digger and set up a post, and put paint on there, or a bottle on there, I’d say what I do is very important to me. Not that I’m important, but the stuff that I do—that post sticking that bottle on that thing—that was a very important part to me.

Now when I put all this together it's just expression of what is important to me. If I just drive a nail in a post, it is important to me. I know I'm not perfect. Man is not perfect. God built the world; man built the Titanic.

I don't make no art to heal. I'm not no healer, but I can tell you where you go to get healed. God didn't give me healing power. Everybody can't be a healer, but I want to build a prayer room here, so everyone that want to go there can go and pray God can heal.

People believe in a lot of crazy kind of stuff, healing and stuff. I'm familiar with them things, but don't believe none of it work. 'Course, if you believe in Christ, he can make it work.

I'm kind of familiar with one thing, that's a horseshoe. When you get ready to go out, they say, "Put you a horseshoe over your door or either hang it over your tree." That's just superstition. But everything have a meaning to it.

Every sickness that a human being have, the medicine is in the woods. Peoples say that the Indians know them but won't tell their secrets about this earth. They'll keep that; they won't tell them, some of the Indians. But mostly I think the Indians is trying to come together and help America, help the world, that there is a cure for every kind of a thing a person have, but you got to know the right thing to get.

My father and my mother, they owned this place since 1925 or 1926-along then, I was about twelve, I reckon. My daddy come from free peoples, and one of his people was a Irishman. That's where the name came from. My mama was a Choctaw Indian, and her mama was full blood. My mama knew all about healing with herbs.

I don't believe much in taking medicine. Most of the medicine I taken was herbs from the ground, my mother made every summer. We used to go to the woods and get the herbs, and get the old kettle, you know, and she say, "Boil it in pine tar and mull it in horse mint." Say, "Come on, get your tea now. Got to get you cleaned out for the summer."

We go out there and get the medicines and boil it down to a tea. All us would come around and drink it, and when it got through with us we was fit for that summer. Hah. None us went to no doctor—none us. My mother raised us, you know, off of this herbs make the tea.

I know a whole lot about herbs. I gather now, and give to peoples for high blood, and for first one thing, then another. Sassafras: that cleanse your blood, that's good for you, but you can't find it now-you can find the white kind but you can't find the red kind. Recent years it died out. We used to have sassafras trees over yonder, going back down to the creek, but recent years so many people had dug the root it died.

You know where to find it now. Yellowroot, and John the Conqueror, snakeroot, alum—all that stuff grow in the ground. But unless people start getting these herbs out of the ground it ain't going to be no cure for nobody.

I got some secrets. The Bible said Jesus went up on the mountain and took his disciples—took Peter, James, and John up there with him. When he come down off the mountain, he said, "Tell no man the secrets," so I don't tell all of it.

There is something in my life I don't talk about it. It might stir up too much emotionally, might stir up confusions, a little misunderstanding. I like to keep it to myself, for God and myself.

And sometimes they say, "What you crying about?" And I say, "You don't know what I'm crying about, but one day you'll understand and say, 'Well done.'"

Whatever my problem is, I keep them to myself. If I'm worried, you don't know it. And if I ain't worried, you still don't know it. There's some things you have to keep concealed, personal. You don't tell nobody. You talk to God.

I like to do something. I like to explore something. There's something always to be done. I put this place here to try to tell the world something: What has happened and is going to happen in the near future; what is going to happen after I'm gone, from generation to generation. That's what I'm trying to do. I'm still trying to explore something.

My place here is black history; this is white history; this is Indian; it is the Bibles, is all creeds and all colors. And I can name all of this stuff, every bit of it, name by name—what it is, what it represent.

But there are some things . . . I got some secrets I don't tell nobody. You don't have to tell all your secrets. There's some of this stuff I don't name. Even if you was to look at it, and if I was to tell it to you, you'd say, "Well, do that make sense?" Everything I got here make sense. Every rock.

They been trying to buy it from me. I told them, "No way. I can't sell it. It won't work." I told them, "I ain't selling nothing here. I ain't selling none of it." Right. I ain't selling none. They ain't going to get it.

See those old rocks up there? Don't nobody know what those rocks represent. That's just old flat rock. But that have tremendous history in it, those rocks. The rocks is very important, but you got to know what to do with them and how to do it. My mind—it’s revealed unto me how to set these rocks, how to place these rocks, how to fix them. I go out there, it's just like laying bricks. It just come so natural to me, you know. Whatever I am doing out here, something is constantly talking to me all the time.

I had the visitation of a strange animal one time come down the hill and I don't know what it was. It looked kind of in the stage of a dinosaur, but it wasn't a dinosaur. It was slick, black, and no fur, and had pretty brown eyes. And when it made a leap, it leaped upon its four legs, you know, like every time he would make a leap he was digging in the ground. When he come up to me, he dead stopped, and I stomped my feet, tried to get him to go away. Wasn't nobody up but me, nobody to help me hem him up or try to see what it was. And when I talked to him he laid down and looked and didn't say nothing. He looked at me, and I looked at him and asked what it was. And then when I quit talking he got up and leaped all around and went across the road, went on down cross the highway there, and I hadn't seen him since. So I said, "Well, I ought to put this in the Centerville Press and see what it is." I said, "Well, they'll think I'm psychic, that I'm losing my mind."

So I didn't put it in there. So I was telling my daughter, and then when they got up, I said, "Y'all sleep late." I said, "Something or another came down to me a while ago, and nobody was up, and didn't have nobody to help me."

She say, "You know, Daddy, that wasn't no animal. Hah. You'll know exactly what was there."

I say, "Naw, I don't know."

She say, "Something trying to tell you something."

I say, "Whatever it is didn't scare me, didn't bother me, but it kind of looked like a dinosaur."

Something told me later, he said, "Naw, don't tell no people.

That was something sacred thing come to you." He say, "This is a Indian reservation. Don't tell nobody."

I still don't know what it was. We got plenty animals come in the yard but never again like it. We got rabbits, coons, possums, groundhogs, deer, squirrels, armadillos start coming (somebody brought them from Texas), chipmunks, skunks around here (but I ain't seen none for a while), flying squirrels. But whatever he was I still don't know.

Taken from interviews with Rev. George Kornegay by William Arnett in 1997 and 1998.