Purvis Young

About

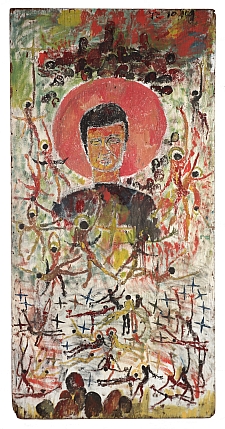

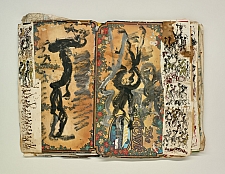

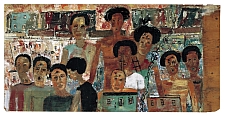

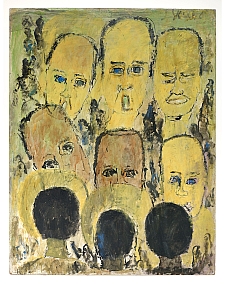

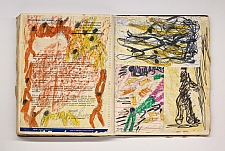

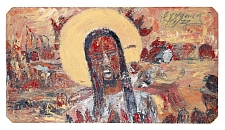

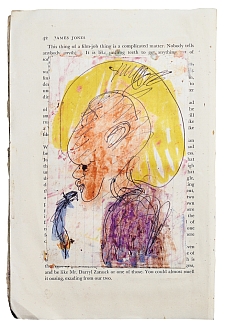

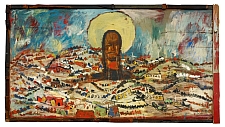

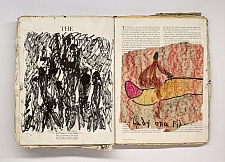

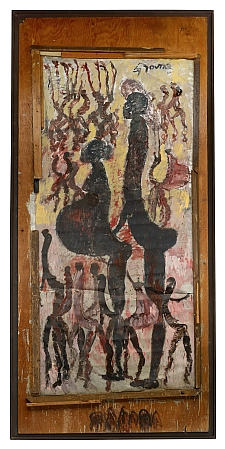

I been drawing all my life, but I taught myself to paint in the early seventies. I seen people protesting. I seen the war going on. Then I found out how these guys paint their feelings up North, paint on walls. Wall of Respect. That's when I start painting like that. I didn't have nothing going for myself. That's the onliest thing I could mostly do. I was just looking through art books, looking at guys painting their feelings. The first things I painted were heads with halos around them.

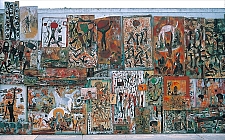

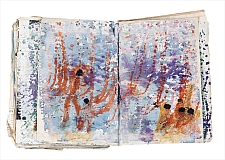

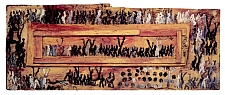

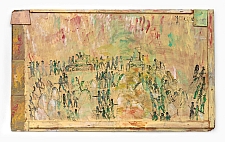

I started out about 1971 in Goodbread Alley. I wanted to express my own feeling. I wanted the peoples to see it. I put my paintings on a lot of fronts of abandoned buildings. They was fixing to tear them down and build an expressway. I knowed when I was making the art that one day it was going to go. Nothing's going to last forever.

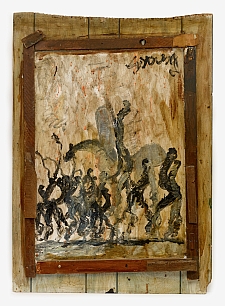

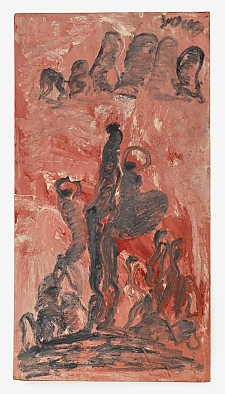

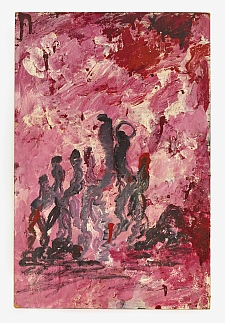

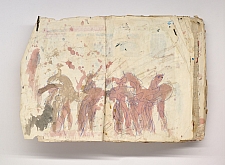

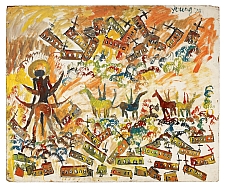

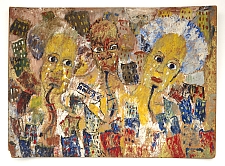

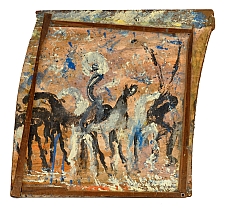

The war was going on then, war in Vietnam. That's when all the demonstrations were going on, protests, protesters sitting in, marching. That's when I started the figure painting, people walking along, knocking each other down, like that. My feeling was the world might be better if I put up my protests. I figured the world might get better, it might not, but it was just something I had to be doing. I make like I'm a warrior, like God sending an angel to stop war. I think, like, I'm one of the figures in my art.

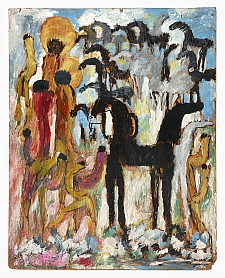

When I started with the figure painting, I liked to show good peoples, the heroes, like that. They fight for a cause. They done good things, they helped the struggle, you know. They're not necessarily just black peoples. I got good white peoples in my paintings. I paint a lot of them white workers. A lot of Quakers, jeopardizing their life, lost their life trying to help black people against slavery. I sometimes have my mind set on John Brown. He tried to liberate the slaves. He died a year before the Civil War. Before that he was a preacher, I guess. I put him in some of my paintings. Some of the white peoples I put in my art are somebody like John Brown. I don't much tell nobody about that.

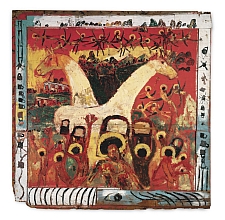

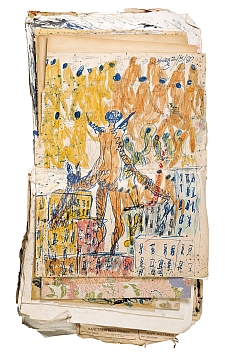

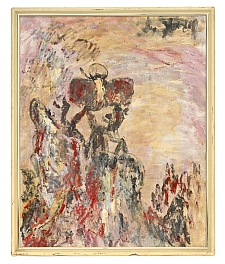

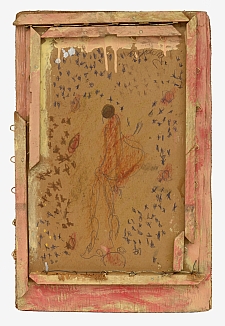

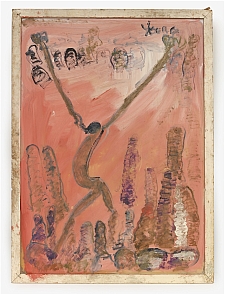

I painted a lot of angels back there. God sends angels to try to clear up some of this trouble on Earth. I don't listen to the Man, I look up to heaven. It's a habit I got. I paint Jesus Christ a lot. I admire Rembrandt, and he painted a lot of pictures of Christ. Sometimes I like to paint where they're taking Christ off the cross.

I painted a few Muslims, too. They got a religion ain't too much different. I always liked the Muslims. I like the Muslim art and stuff from that part of the world, like India. I get a lot of ideas from that part of the world.

I had taught myself to paint back then. I liked to draw when I was young, but I stopped doing that, and when I was in prison in the sixties I started drawing again. And when I got out I taught myself how to paint. I taught myself that each brush means something. I just used my mind. One day I looked in a magazine and seen the way people paint their feelings, and I started painting and went from there.

There's alleys all around that neighborhood. Goodbread Alley was just another alley. But it was a hell of an alley. Police wouldn't go into that place back then. They wasn't taking no chances. A movie called Bucket of Blood was made about it, I hear.

Shotgun houses used to be all around that place. Some people took good care of their houses. They were proud of their houses. But they all looked alike, you know, and the city had a problem with that, and tore the houses down. And they built apartments to take the place of the shotgun houses. They was just a bunch of old wooden houses, all looked alike. Things like that, it made me want to express my feelings. It was up to me to put up how I feel about stuff, like the protesters did. People told me that if I did that in another country, I'd have disappeared.

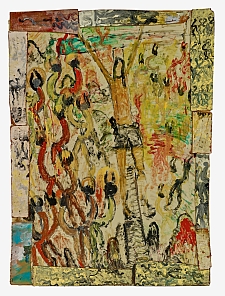

Every day I came and find wood, you know, and put it up on a wall and paint it there in the alley, right off main street, 14th Street. Sometimes I dragged old crates down, you know, those moving crates. That was the biggest I would do. Sometime people would come swipe the paintings. I put a lot of early ones away, but a lot of them just disappeared. I didn't care if my friends take them, I just put another one up. After about two years people started driving in there to see the alley. A lot of tourists. Sometime they would buy a painting right off the wall, put it in their car and drive away. It was mostly white people interested. Some people would say stuff, say I looked like Gauguin, all different artists they say I looked like. A lot of black people seen them but they didn't say much to me about it. Some of them said I was mad, some cursed me out, some said I was sick. Some liked it, some of them admired me, some didn't. A friend of mine—he's passed away now—say to me, "I look at your paintings but I don't see nothing. But every time I turn around you're in the newspaper."

Some of the people that came to Goodbread Alley, they seemed to understand my paintings. Some of them I had to tell about it. There's a lot of stuff in my paintings people wanted to ask about back then. Like locks. I put locks in some of my paintings. A lot of people are locked up, struggling. The lock is playing a key part. It means mostly something's wrong.

Goodbread Alley had a lot of people from the islands living around it. I was born there, by the alley. That's where I grew up. My people was from the Bahamas. I don't remember art being made by any of them, but I asked my sister a few years ago and she told me stuff. She say my uncle tried to do what he call "turn old wood into new wood." I knowed something was weird about my uncle, my grandmother kept him in a place, like, locked up. The police came for him a couple of times. I asked my sister why he was kept like that and she say he was an artist. My uncle like to paint birds and stuff on the wood. I never seen him do it but my sister saw it. There was a tradition in the Bahamas, where Grandma come from, Bahamas got a tradition for getting children educated. My grandmother wanted my mother and my uncle educated. My uncle didn't do that, and my mother she just wanted to run with a crowd. So my grandmother kept them apart. She never wanted her other grandchildren to play with me, because of my mother having no education. She must be afraid I would have a bad effect on the others. She would feed me and then run me off. But the other grandchildren have all died young.

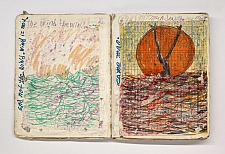

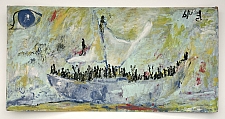

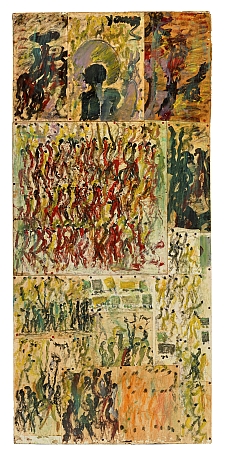

I have painted a lot of boat people. I mostly see the boat people struggling. I see them on the news, where the boats turn over, or they get turned around, sent back. Sometimes I put sharks in my art, boats turning over with sharks around. Sometimes sharks keep peoples from getting to freedom. Sharks let you know it's dangerous coming across to Florida. Sharks are part of everybody's environment.

When I was a boy, my grandmama make sure I heard the story. I heard my grandmama tell how she eased over to America on the boat. She come from one of them big British islands, and I just heard her say how she got here. The white man didn't want black folks, most likely, coming to America. It's in my mind, that's my belief. The white man don't want black folks to come. So I always wonder: Would the white man get concerned about white folks coming to America? Always puzzled me.

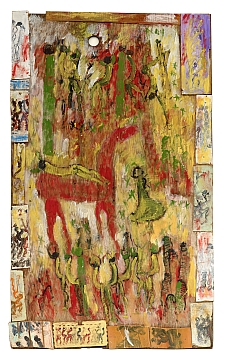

I always liked to draw and paint horses, wild horses. I just use horses mostly for freedom. I love to paint wild horses, freedom horses, wild horses running free.

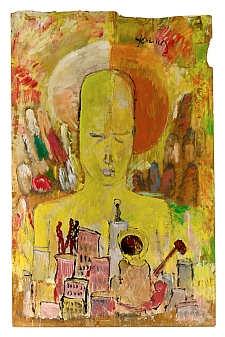

Everyday I see in life pregnant women. I try to tell in my paintings that the pregnant woman is the birth of the earth. She represent some of the problems I see in the city. She's given birth to some of the characters around. But the way I feel about it is, they're all giving birth to angels.

I paint funerals and graveyards because I see a lot of my friends pass. I been to a lot of funerals. I paint angels coming down to bless the peoples; guys carrying caskets sometimes; angel sitting on top of the caskets. Death to the people. Good people become angels. I just paint good people. I don't know what happens to the bad ones. Sometimes when angels have come down to try to tell bad peoples what to do, they have hung the angels.

I like to show railroad tracks. They always build colored town by the railroad tracks. When I was a boy we'd go to where the train was just parked there and we'd open the watermelon cars. I'm thinking that watermelons are real valuable stuff. We'd open the cars and run with the watermelons. That's what I remember best about railroad tracks. When I was a boy you could tell colored town by the railroad tracks going across, separating the whites from blacks. Lots of times blacks was the ones built the tracks, like for Mr. Flagler on Florida's east coast. One way of knowing your environment is understanding the history. Blacks couldn't ride except on the back of the train, couldn't live but on one side of the tracks. But now the trains have come to mean freedom.

I see guys working, making a living with trucks. I love to paint trucks. The truck taken the place of the horse and buggy. The truck make works for the peoples. I create about the works.

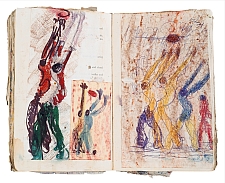

I love sports. Sometimes I hate to lose. When that feeling get me, I do ballplayers, reaching up, trying to catch a pass, happy to be playing, happy to be winning. Playing in the projects, sometimes that's all they could do, one way of passing time.

I like to paint soldiers. I like to do like Remington sometimes. Remington loved to paint soldiers. And I want to know if I'm painting the truth sometime. I seen a commercial come on TV and that young soldier say, "This is the army, not Hollywood." I been listening to Hollywood all my life. Now I be listening to documentaries based on true stories. And I was shocked—because a black dude told me this—I was shocked to know the Chinese fought America to a standstill. But a black man had to tell me this, a black guy told me, say, "You know, Purvis," say, "you know, America put something on the Koreans, but when it came down to China it was a different story." And sure enough I seen it on Channel 2. Stuff I'm still learning.

When I paint I want to know if I'm telling the truth, if I'm listening to the truth or what.

As I get older, man, I'm getting to find out some things. I see how Russia played a key part in World War II. And black soldiers, too. I heard about the black army. I heard a black lady was talking about a cemetery for them in Miami and she say if she don't tell it, ain't nobody else going to tell it. Some things you just don't see in the history books.

I'm getting to find out, man, about history. When the white man tell history I'm getting to find out it's kind of a little different, you know? What shocked me . . . because I like to paint soldiers, I look at the last days of the war, documentaries Channel 2 show. America was throwing big guns at these Germans, and Germans was throwing it back. All these warships out there. And it land of puzzled me. I looked at how Mr. Roosevelt sent this certain guy- and this guy made a secret run to Russia. And Mr. Roosevelt made sure Russia got what she need to fight with. How Russia fight house to house. I seen this, you know. Ain't no Hollywood stuff. Man, I was shocked when I seen this. But Hollywood always want to show me John Wayne.

Russia fought hand-to-hand with the German soldiers. And I was shocked 'cause all I know was what the white man tell me. That's all I know. And all they tell me about Russia is Marxism stuff. I ain't no Marxist, man, but it say something. And Channel 4 showed a documentary, showed about Stalin and Churchill and Roosevelt, and I heard Stalin say, "You know, it going to get cold after a while." He told Churchill that and sure enough, when it got cold, Russia had built a certain outfit that fight in snow.

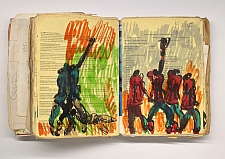

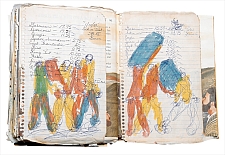

I get me all the books. Different artists I liked. Rembrandt, he walk around, paint a lot of Christian pictures, you know? Gauguin. He all right. He got tired of seeing the same thing. He left his wife. He was a merchant marine, too. Traveled all over the world as a young man. I just like to read about painters because they have the same problems. Same problems. They look like they see the same thing I see.

All at once, as I get older, looks like these characters start coming alive in these art books I look at. Some guy might have a wine bottle, and sometime a guy might walk down my street and I say, "That looks like something out of art books." Sometimes I look at buildings and it seems like the buildings come out of art books. As you get older, you see more.

I try to learn everything I can from the books, documentaries, and everthing I got to know so I can paint the truth. I walk around and look at the peoples, too, see if the peoples are happy. I looked at a lot of art books. Mainly I looked at the backgrounds. I'd learn something from what I see in the backgrounds. Like the landscape. Like the little figures. I see the same thing every day, little people I see every day on the street, they look like the little figures in my paintings. Everything in my paintings, just about, come from the neighborhood.

I used to see everything that go on in the Alley. The Alley ain't there now, but what go on now be about the same, man, every day.

I get a lot of my ideas sometime just riding my bicycle around, just looking at reality, looking life right straight in its face. I walk, or either ride my bike, and look at peoples hanging around the buildings. I try to catch them in their environments and try to paint what I see. If they're not happy sometimes, I paint it like that.

The buildings are where a lot of problems are at. That's where the police arrest peoples. I put that in my paintings. Sometimes I see things I don't like. Sometimes homeless guys pushing buggies. I been seeing this all my life. Some of them got drug problems. All of them got some kind of bad problem. Guys doing this, it's what I see every day in Dade County. Bring back memories. I been seeing it for fifty years. One guy got a buggy he done made like a freight train, pushing a lot of things in that buggy, things he finds; sometimes he stops traffic. I look at it that all those guys are angels. Good guys with bad problems.

What I see, I see Christian people all around where I live but the churches are barred up like jailhouses. I see it as the preachers and the drugs. I make paintings about it. I tell myself, "Purvis, try to master what you don't like."

I don't like the luxury I see of a lot of these church people while the world is getting worser. What I say is the world is getting worser, guys pushing buggies, street people not have no jobs here in Miami, drugs kill the young, and church people riding around in luxury cars. This is my belief: As I get older I look up there in the sky and I say, "Thank you." I don't believe in these church people. With all the world problems the church don't pay no taxes. They're just part of the system, you know. The Church, some folks in it thought that slavery was alright. I look up in the sky and say, "Thank you." I don't follow man on earth.

I look at medieval times and I see history, it repeat itself. I look at ancient history. Same thing now. I seen a motion picture about a Roman soldier. Told another soldier, see, a barbarian had spoke to the Roman soldier so the soldier told his friend, "Man, you going to have to make friends with the barbarians." That's what I see here in Miami. I'm tired of seeing the same thing every day, all my life.

All my life I listen to white folks tell me about freedom, you know? And I got a feeling that when I see the rich get rich and the poor get poor, I don't think it's such a thing as fighting for freedom. I see that country where America just fought the war, Kuwait, and they ain't got no justice in that country. They got kings, send their sons over here. America got puppets too, that's my belief.

I feel like this: I ain't never asked these people for nothing. I ain't never asked the government for nothing and never will. I feel proud of that. I been listening to mostly white peoples all my life, telling me everything in life. Now I'm in my fifties and I have reflexes. I look on TV and my mind starts to play tricks on me, because something tell me, "Purvis, the white folks showing you black folks like Michael Jackson for a reason." And I don't look at that. Show me peoples like Michael Jackson and black folks selling these white folks' stuff. And that's my opinion. I'm just the way I feel, because I'm older and I been thinking the reason why the white man show me black folks like this is to sell his products.

Look around here. Guys getting killed all around here. Guy walked up to a guy the other day—guy sold him some bad stuff-boom—blowed his brains. This goes on all the time. I don't think things get better because I think the white man want black folks all messed up. But the only thing, when he see the white kid on stuff, he want to do something about it, you know. It's always been on my mind. I buried two brothers. One of my nephews died of AIDS. One of my nephews is doing twenty-five years, and that all in my family, I don't think the white man wants it to get better. I been doing the best I could. I'm still going to say it: If you ain't working nowhere, and you're on drugs, how the hell you're going to support yourself? You're going to rob me or you or somebody. This is the life I see.

Taken from interviews with Purvis Young by William Arnett and Larry Clemons in 1994 and 1995.