Emmer Sewell

About

Emmer Sewell describes growing up in rural Perry County, Alabama (near the town of Marion), and her early exposure to work, art, and music:

“You know, I got around six or seven sisters and seven or eight brothers. All the girls picked cotton when I was little, soon as they was old enough. The little ones like me didn’t turn in much, but I was up to doing more. I come in once with a hundred pounds of cotton. White folks noticed that. They told my grandaddy, “That little child, that little picker, pick a hundred pounds! My lord, she a working person. She going to be a good working person when she grow up.

"My life growing up was wonderful, beautiful. I used to be always going in the yard and make these things, like when there was wet dirt I put my foot up there and make pictures with my foot, and make a hole through the wet dirt, like you ram your hand in it and draw. I would make pretty things like that. I made dolls, too, and other little toys and things, and I get my pencils, you know, and make pictures of pretty things, people and flowers and stuff. I do things like that when I was little. I tried to decorate things as it was. Whatever you see it, I had knowledge of doing, from a little child, you know. I put sticks together in the ground, stuff in trees, drawed things everywhere. You can think of many ways to make things look pretty.

"When I was around about nine or ten years old, eleven going into twelve. I used to love to sit at the piano and play it in school. I be in there playing that piano, and the teacher so glad I could play it like that. And I was sing, sing, and be an actor. They wanted me to get where I could stand up and be brave and say speeches on the stage. My uniform was always a white dress. And I’d get me a 100 in my arithmetic. I had this long hair and was nice looking back then.

"Mama and Daddy and them was raising good old food. Had plenty of corn, cotton, peas, potatoes, peanuts. And cows. Milkcows. Whole lot of milk. We’d churn milk, you know. Whole lot of chickens. You couldn’t pick up your foots and step through the yard. I growed up back over by Hopewell Church, just like the place I’m staying on now. Had a whole lot of hogs. Kill five hogs every winter Me and my sisters strip fodder for the cattle in winter when the cotton season over; and I do good bottoming chairs with the shucks that come off the corn.”

For many years Sewell has been gathering “just junk from here and there” and turning it into sculpture throughout her yard. Few people comprehend her works, and she has always been reluctant to discuss her motives for making them. “I just pick up junk and piece it together. It ain’t nothing but crazy stuff. But,” she adds with pride, “I got just about the cleanest place anybody ever seen. I keep this yard so clean you could eat your food off the ground. Even this junk I made outdoors, I always keeping it so cleaned off.”

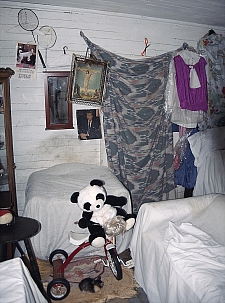

Sewell is as proud of her house's interior as she is of its exterior. “Inside the house every inch is so clean, everything covered up, Snow White-clean. My walls, they got stuff on it for me. Jesus Christ—he’s so important. Anybody that’s a Christian, you would like to have Jesus Christ in your home.” Her wall of respect also contains a portrait of John F. Kennedy, which she hung after his assassination.

Autobiographical references abound: badminton racquets (“we played when I was in school”), a picture of a dog (“always did love my dogs”), coat hangers and scissors (charms), a mirror (“see yourself, respect yourself’), her church choir outfit, and a picture of the crucified Christ (“Jesus Christ control it all”).

Neighbors appreciate her meticulous care but usually misunderstand the purpose of the art in her yard. They believe it must be what she calls “hoodoo-voodoo,” which makes them nervous. After keeping her ideas private for her entire life, Sewell, now in her sixties, has decided that it is time to express herself verbally so that others may understand and benefit from her work. Her imperative regarding these disclosures is to “bring it out now in the knowledge of me.”

Sewell says, “If folks will think over many things, they will move in God’s direction and try to understand other folks better. I do what I do in sensely ways and not crazy ways. Other people thinking, you know, it’s what you call ‘the devil’s side’—his fighting side—but it’s not. You can look at it a-many different ways, you know, and kind ways about it, ’cause I just arrange stuff to make my yard more beautiful. It ain’t got no mean semblance. It’s about the Lord’s Gospel messages.”

Her seemingly obsessive maintenance and cleaning of her yard, including the daily raking of the dirt portions on the side and behind the house, is actually in keeping with the old African American tradition of the “swept yard.” Her family has kept that tradition alive.

“Keeping my yard real clean, house real clean, I was raised up that way. My parents raised me to do it. They did it that way theirselves, and their parents did it that way. Clean bed linens, clean mattress on the beds. We couldn’t layup in nothing that wasn’t clean. You had to have your food to be spotly clean before you sit down at the table and eat it I rake up the yard, and around the house, under the house. Anything that’s built would be yours to care for Papa used to have us going up under the house, cleaning up. He didn’t want no filth up under the house. And our yard was just like that highway; wasn’t no filth nowhere around.

"I try to do the best in my yard I can. Rake it up, and no snakes and things. Snakes won’t come up in my yard. They stay down there in the woods under the brushes and everything. They curl up under there. I could see them if they come up here, and they stay away from here.”

In Africa and the Western Hemisphere, keeping snakes away from the house has been one of the major motivations for the swept-yard tradition. Sewell employs several traditional anti-snake devices throughout her house and yard, such as the strategic placement of sulfur.

“Put it in the corner, each one of the corners, all the way around on the side to the wall. Sprinkle that sulfur. You can sprinkle some on the outside around the building. Wouldn’t a snake go inside that building, wouldn’t no rattlesnake come nowhere near.”

A number of hardwood trees throughout the property have iron spikes, rods, and machine or tool parts driven into them. In combination with the iron are pieces of wood from nature or from discarded furniture and a variety of other materials (metal foil, glass, cloth scraps, can lids, and occasionally, paint or pigment).

“I got them things drove up in them holes. And I got some bottles and some other stuff drove down in there, in the tree and in the ground around it. You know, snakes go in those trees, and I put that in there to keep those snakes from coming out.”

Snakes are not the only threat to the security of rural residents. Among many of the world’s cultures, including African and African American ones, there is a belief in the need for propitiation of the spirits of the dead. Protective charms are one method for dealing with the presence of wandering dead souls (“haints”); such devices are found in African American yards throughout the South. They are less plentiful now than in the past, but they are still abundant. Charms, accumulations of various materials arranged into any form that suits the charm’s maker, are conventionally attached to trees or houses, or placed in the ground. Many charmlike assemblages are found throughout Sewell’s environs.

Does she believe in spirits? “You needn’t be a-scared of the dead. It’s just because the dead ones is going onto where they going. The dead is gone. I’m not afraid of the dead. If you’re Christian you’re not afraid, if you be born again and got Jesus in your soul. That dead stuff is just superstition.”

Or perhaps not. When Sewell decides the question about her belief in spirits is not meant to be a trick one, she allows,

“Well, there is this house across the road in the other side in front of my house. That was a great big old white-folks’ houses it across that road, but it rot down. Colored folks was staying in that house. Those that was staying there knowed me when I was a little child. I was loving to them—no hatred. And they died. All of them dead that been in that house. And I’m not no afraid of them. And I can hear them talking out there at night. Dogs be barking over cross the road, you know, every night. Dead folks, talking and going on. I can hear them, folks which done up-and-died. I’m not getting no more afraid of them.”

Other protective constructions stand or hang. In the woods a red jersey suspends from a forked stick, beneath which an inverted glass jar is embedded in the ground (“Red thing hung up like on a cross”). A bright red cloth is tied to a tree branch near the highway. (“Blood red, a sign for folks coming down the road. Say, ‘Slow down, drive careful,’ like a traffic light, you know. You go on green, you concentrate on yellow.”

Some assemblages consist of mementos from Sewell’s past, which in combination form powerful tree charms. Concerning one of them, she says, “I hung that up in that tree for good luck. That wire basket was a lampshade. All the good stuff done come out from around it. The piece of cloth that hang down was a little duck I bought from a white lady and put lace on it. It’s like Snow White to me, like a piece of wedding dress all tore up and rotted now. That gourd was give to me by a heavy-built white man, insurance man, name of Lewis Levitt, stay in Selma. Piece of iron came off a plow what our old mule pull. You hook up the plow, then hook up the mule by a chain. I picked it up, it was like back in time when folks had mules and plowed with them. You see the old mule shoe and a piece of old Chinese fan: all is stuff you need.”

A charm adorning a tree at the beginning of a path into the woods ensures safe travel down the path. It combines a piece of automobile chrome, the remains of an ancient suitcase, and a wire cross: “Piece of stuff come off my old car; old blue suitcase something I put up there so as to not throw it away; the cross thing I found.” The color of the suitcase (sometimes called “haint blue”) is widely believed to repel menacing spirits.

A cluster of outworn appliances and kitchen accoutrements, carefully placed and periodically rearranged, also “guard” the path. Among the many components are an “old deep-freeze from when I used to work in the house where this white man stayed, a shiny pan you can make chicken dressing in it, this old stove laying down, a whole lot of jars and a bunch of pans, a thing you wash dishes in. I got all that mess out of my kitchen.”

Standing near the roadside to provide would-be trespassers with food for thought are her private protective figures, two scarecrow-like effigies that wear red hats reminiscent of the berets of New York’s Guardian Angels. These figures, according to Sewell, are actually based on “the Black Panthers out there in Hollywood. They’re famous when they was tearing up things out in Los Angeles, out there in California. Folks scared to go to them. They was turning over cars, breaking windows out, going in stores getting what they want. Sheriff been scared to arrest them. That’s a mean, mean game, you see. And folks just stood up and let them burn what they want, and tore up what they want, and sheriff was scared to go to them. If you ever come in contact with them, you know, get a fight with them, they’ll kill you. Peoples know about it. If they see it they know what it mean.”

A row of five sculptures faces the two-lane state road in front of her house. Each is there for a particular reason. The first piece, the one closest to the road, serves as a landmark and caution sign. It is constructed of “a big old iron with that artificial flower in it and a little pipe holding that flower. It stand there so folks will know to turn into my little part of the dirt road, not take the wrong fork that go down by the spring. It also got to warn people to get away from the edge of the road, that it’s dangerous running off in that gully where the garden is.”

Next is her mailbox, which has evolved into a strange sculpture with cups atop posts, fragments of bricks and cement, wires, and slabs of wood. She traces its inspiration to the Old Testament: “The Lord is my shepherd. I shall not want.” She continues to recite the Twenty-third Psalm, approaching its end: “‘He anoint my head with oil. My cup runneth over.’ You see them cups? You see the box? You got to do what? To dwell in the house of the Lord forever, that’s what.”

The third piece consists primarily of wooden stakes and a metal folding chair wired together, to which plastic beach balls and a man’s cap are affixed. “It’s about young people doing stuff, playing basketball, throwing in the goal. It’s about children learning things. That’s a ball you take with the little children when they go swimming in the water. You get children so you can teach them.”

Sewell’s signature piece, the fourth of the five, stands nearly six feet long and over five feet tall. Its components include metal chairs, wooden boards, a plastic “tray for light bread,” a ceramic vase, a forked stick with three red artificial flowers pinned to it, and in the center, a sign painted with a mysterious symbol, an X with a dot in each of its quadrants. The same ideogram is found throughout the yard—for example, on an old inoperative car and on an abandoned refrigerator in a grove of trees—and is reflected in arrangements of chairs, tables, and bric-a-brac elsewhere. About this piece, and about her art in general, she says, “Women go through stages. You know about that. Children being born out of any woman. Children grow, you know. Women teach and bless.”

She sees her art as something that gives birth, evolves, matures, protects, commands respect: consummate personal female metaphors.

“You go to a doctor. You know how doctor got signs up all about his place to recommend his place? I got my signs, too."

She elaborates on the various messages contained within the assemblage. To explain the forked-stick segment, she begins to sing gospel style,

Yield not to temptation.

Jesus will carry you through.

Ask the Savior to help, if a victory will help,

Jesus will carry you through.

She then explains, “That V is for victory,” adding that “if you’re a Christian person, you remember the symbols of God, you see, and use them. I can sing them. I can build them.”

She wants to explain her secret symbol, the one misunderstood by so many, so often.

“That cross is nothing to make a fuss about. You can see the same thing in a lot of places. It’s not nothing for nobody to be alarmed about. It’s not dangerous. I put it on refrigerators and those things—symbols of God. You’d be proud to be as what it is. I put it out on the car, you know, so if they ever sell the car they know whose care they sell to a person. It’s kind of like a Roman number that you had in your schooling days. That is a sign of history. That sign is a great symbol of things. It’s no mean thing to it, nothing devilish in it. It is not. I is a symbol to recognize by. It is a symbol of recognized ways.

"You watch Oprah Winfrey when she be running her show; watch her picture sometimes, when she come on at four o’clock. She got that same X on her place. It mean ‘important work.’ ‘You could be somebody.’ It mean ‘reaching for the stars.’ If you ain’t got no common knowledge, and don’t carry yourself in the right way, and learn nothing, you can never be a star; reach the stars. Never, if you got filthy ways and stupid ways.

"Them little dots in it make it a star. Let you know you got good running. Knowledge can make you be a star You can use your knowledge and background.

"Look at it another way: It’s like Jesus Christ nailed to the cross. You can have all things. You put your trust in him. Listen to me sing and you’ll get the word what I’m talking about."

She finishes her point by singing a few lines from "Que Será, Será,” emphasizing the question, “What will I be?”

The final piece is only a few feet removed from the other four. To a post erected by the telephone company to warn of an underground cable, Sewell has added a wood bar, cups, bricks, and rings of metal, intentionally suggesting bicycle handlebars and a rough road. She seems to be trying to establish symbolic control over, or protection against, the encroachment of big business and technology on her rural privacy. Her somewhat enigmatic explanation: “Hold your hands like a bicycle to ride. It’s a warning of danger. It's in the ground. It runs under the ground to your house. You see dangers in it. That’s the telephone folks’ business with that thing, not my business. They’re the ones put it out there. I did what I did where other people could see something that was dangerous, could know what to do with it”

When the telephone company encroached further upon her yard, Sewell quickly applied more neutralization tactics: symbolic pieces of iron (a horseshoe and a plow part) and a vertical row of Xs painted with the traditional haint blue. Sewell explains, "Telephone company business office, they put a great big box to my telephone. It was a dangerous box. They put it there by that telephone post. And I knowed about that wire in the ground around that post. I made them got it off, take it down there by the fish pond. I made them got it away from my house because it was dangerous. I put a horseshoe on there, and a piece of iron, and some of them cross signs.”

One assemblage stands out. It is Sewell’s monument to faith, a white plastic chair perched on a white-painted automobile tire. A chunk of cinder block has been placed in the seat. Again, she sings a sort of free-form improvisational gospel hymn:

I am going through.

I’ll pay the price.

I’ll take the way

And fly into the sky.

So many, they started out

But didn’t make it through

Because they turned away from Jesus.

Go along with Jesus:

He’ll see you through.

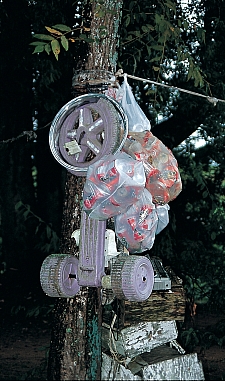

Nearby a purple plastic tricycle hangs from a tree. The toy is surrounded by bags of empty soda and beer cans, and is a statement about children’s health and safety. Like all other assemblages in her yard, and in the fields, and on her porch, this one changes forms regularly, prompted by Sewell’s intention that her creations continually evolve and respond to changes in her moods and attitudes. “I see things in a different manner,” she says. “A new definition come. I don’t want to see my yard in a constant way.”

On her front porch is an assemblage featuring a painted pottery vase of traditional European form and a ceramic goose. Added to the two primary elements are shoes, an aluminum plate, a toothpaste box, and an assortment of everyday trash. She discloses its meaning by singing a parable about Christ that begins,

Jesus met the woman at the well.

He say, “Woman—

Look here, woman—

Tell me where is your husband.

“She say, “Lord, oh Lord, I don’t have one. . . .”

And then she further explains, "That vase be the well. That duck be the woman. Them shoes be the Lord's feet."

One of Sewell's several cats, the oddly named female, Tiny Bubba, likes to watch outdoor activities from inside the house through an eight-paned window that exhibits photographs of family and friends juxtaposed with souvenirs and mementos. While this type of commemorative display is very common in African American homes, Sewell's unusual inside-out version indicates a proud, extroverted woman willing to reveal herself to others and share herself with the community. She has remarkable awareness of the implications of her creative efforts. She turns a normally private, household altar into a portal directing her experiences toward the outside world. In so doing she demonstrates to others, especially any suspicious neighbors, that she is an ordinary, safe person. To white people who could be potentially dangerous, she gives proof of her longstanding relationships with whites, especially white children, and of what she describes as "the white part of my family. My grandmother, she was a white lady."

Around Sewell's front porch and inside her house are decorative borders and collages of toothpaste boxes and spent toothpaste tubes. It serves her purpose well that the current brands (e.g., Colgate, Arm & Hammer, and a newer, expensive brand named for a Dutch painter) boast of their "whitener" ingredients. She continues to enumerate her many methods of ensuring cleanliness, ending with "you got to keep a clean mouth. White teeth proves a fresh mouth and a clean heart."

On her side porch she has made a sculptural directive to parents. It is a white stool standing upon a homemade table whose imagery suggests, according to Sewell, "when it was a little child sit up at the table. That's a iron stool sitting up on it, and just to let you know it was a child sitting. You know that children supposed to sit at the table when they get a certain age for eating. Parents got to respect children and teach them. Teach them good manners." She editorializes and instructs: "Old folks will know things young generation don't know, don't know things like old folks know. Our generation was glad to learn things. When we was little they explain stuff like that to you. Like what to do when a storm arrives. What you do, got to put a ax in the ground and turn it straight to that dark cloud. When the storm comes, that ax will split that storm. Part of it will go one way, part will go the other way."

Ax blades are attached to bushes elsewhere in the yard. Sewell points to one of them and explains:

"I was raking off the yard. Found that old blade. Didn't have a handle to go on it—it's so rusty and all—and I say, 'I ain't going to throw you away; I'm going to sit you up there on that bush.' It represent, like, you know, 'Davy Crockett, King of the Wild Frontier./ Raised in the wood, he know every tree./ Killed him a bear when he was only three.' Remember that song back then? That old ax stand for your knowledge, your background, where you come from, a person's history. If you're raised up from a little child with knowledge, it'll carry you when you're grown. A person got to defend themself, too, to get on."

Like many African Americans in the rural South, Sewell uses chairs, stools, and seating arrangements in her front yard in ways that are widely understood to indicate honor, respect, and hospitality. Chairs play many symbolic roles in the African American yard. A lone chair, sometimes adorned but often humble and plain, can stand for the throne (and presence) of Christ and, as such, often receives prominent placement. Similarly, the chair can symbolize the spirit of a cherished ancestor, or community leader, or friend, thus providing a demigod-like form of protection. Most often, though, such seats are used as a sort of welcome sign or subliminal invitation: "I am a person who invites you into my yard and home."

There are seats and seating arrangements in Sewell's front yard that are rearranged almost every week. No one sits in them. (Such seats in African American yards are seldom intended to be used. They are yard dressings, placed as emblems only.) If the rain does not wash them regularly, Sewell will. She wants visitors to know that she is clean, hospitable, and harmless. Those who enter her yard, however, see more than chairs. There are strange assemblages, manipulations of branches and vines, crossed twigs and forked sticks, ground charms and tree charms, and personal symbols. If visitors are attuned to the old ways, they recognize that she also is a learned elder. They comprehend her complete message, which is that she is a gentle and friendly woman, yet if you come to her for the wrong reasons, she knows how to deal with you.

Beyond her house and yard, through thick bushes and trees and down a hill, is Sewell's garden. It is on the edge of a gully covered with vines near one of the tallest, densest stands of trees in the vicinity. Throughout the garden, in and around it, are a number of simple but beautiful works of art. "They there to scare the deers away from the garden. Deers, they slip in here at night and make a mess eating up things," she says.

Sewell's "scarecrows" play an interesting dual role in the lower garden, around the outside of her house, and in other non-garden locations. Each of Sewell's assemblage scarecrows could illustrate a sourcebook on traditional African American protective charms, commemorative sculptures, healing devices, and African retentions in the Western Hemisphere. Each scarecrow contains some of the requisite components: roots and natural wood formations, bottles, cans, cloth, and subtle references to ancestral nurture and guidance (parts of bread or milk crates). She ascribes to them the ability to frighten vegetable-eating predators but does not say why so many scarecrow-related objects appear in places where no crops were ever intended to be grown (such as beside the road). Her best explanation: "I just put them things out there." What things? "Them guards."

So if deer or squirrels or birds come, Sewell is protected. If people or bad weather or spirits come, Sewell is also protected.

Nearby is an elaborate line of sticks and branches artfully arranged and tied together. Collectively, they demonstrate the ordered chaos of many African American forms of expression. It is an approach to formal arrangement that appears frequently throughout her works on the property. Anticipating an enigmatic or metaphysical reply, an interviewer asks Emmer Sewell, "How did you decide which way to put these sticks?"

"The snap beans are running up," she reveals. "I stuck them sticks that-a-way-the way the beans were running."

In the trees behind Sewell's house is an indescribable piece of what could be called contemporary improvisational vernacular architecture. It is actually a split-level, partially subterranean doghouse built by Patrick Sanders, Sewell's father. A dairy employee, Sanders made the doghouse in the mid-1960s, and after his death in 1971 Sewell continued to keep up the structure, adding decorative elements as ideas came to her. And as dog after dog lived out their life spans, Sewell kept embellishing the doghouse. Why does she need to keep a dog confined at the edge of her backyard? "Just to let me know stuff," she says. "It get dark down here at night, you know."

Quotations in this article are taken from interviews with Emmer Sewell by William Arnett in 1997, 1998, and 1999.