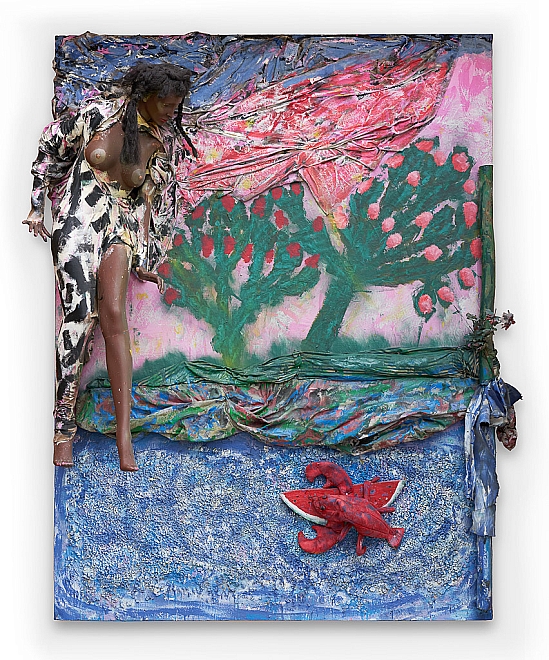

Choices/Sunrise

In 2003 Dial accompanied his friend and fellow artist Lonnie Holley to the Birmingham Museum of Art, where an exhibition of Holley’s work was on display. While there, Dial saw the painting L’Aurore by French nineteenth-century Salon painter William Bouguereau. A sensual, romantic rendering of the mythological goddess of dawn, Bouguereau’s painting revels in the classical Eurocentric vision of the female form as idealized beauty. Voluptuously draped in a flowing, diaphanous veil, the goddess hangs suspended over a tranquil reflective pool, mediating between daybreak’s brightening sky and the darkened landscape of the fleeting night. With her right hand, the figure grasps an elegant calla lily, a symbol of rebirth and new beginnings.

Dial’s response to Bouguereau’s L’Aurore is his painting Choices/Sunrise, a work that in many ways mimics its historical source but also expresses, both by its title and its iconic elaborations, the contrasting sensibilities that mark and measure Dial’s view of the world. To begin, Dial has replaced Bouguereau’s painted image of a white female figure with a black store mannequin that appears to be stepping out of the painting’s picture plane. With an ironic nod to primitivist visions of African American beauty and sexuality, Dial drapes his female character in animal-spotted cloth. In further contrast to Bouguereau’s image, Dial’s figure is no longer the only subject of the painting. Moved to one side of the composition, she gazes at two strange objects—a slice of watermelon and a crimson lobster—which float together in the pool of water before her.

Highly charged symbols within the lexicon of African American southern culture, the watermelon and lobster represent the opposing worlds of the country and the city and the quandary faced by many African Americans of Dial’s generation about where to seek life’s opportunities—in the quiet, rural existence of the farm or in the “high life” of the big city. As if to mirror this conflict, Bouguereau’s calm reflecting pond has now been replaced by Dial with a turbulent ocean that offers no quiet contemplation but rather the agitation and anxiety that come with the choices that he and other African Americans have had to make in response to the social and economic challenges historically confronting them. Similarly, Dial’s sky contrasts with Bouguereau’s placid and ethereal atmosphere. Created from a mass of old fabric bundled and scrunched across the top of the picture plane, it boils in waves and eddies of harsh and contrasting color.

While Bouguereau’s picture evokes a transcendent and universal quality, Dial’s version is rooted in the local, the political, and the here-and-now. Bouguereau’s goddess is an alabaster vision, ethereal and untouchable, an aesthetic emblem of empyrean beauty and truth. Dial’s figure, on the other hand, is a broken and discarded mannequin, the literal embodiment of the tradition in black art that expresses itself in found objects, recycled materials, and discarded bodies, those materials relegated to the trash heaps of culture and consciousness. Moreover, as a figure formerly used as a commercial display, Dial’s goddess is representative of the vicissitudes of a commodified culture in which value and beauty are established not on high but negotiated in the marketplace—where everything, especially black people, can be bought and sold.

Dial was probably attracted to Bouguereau’s work because of its focus on the feminine form, a subject that Dial has explored frequently, especially in his drawings. But in reacting to Bouguereau’s painting, Dial transformed it. He tropes contemporary critiques of the objectification of the feminine by re-presenting woman as actual object, no longer contained by the two-dimensional representations of pigment and canvas but literally emerging into the world of embodied form. In this way, Dial’s dark muse defies the gaze, empowers herself, and sets her own sights on the choices she must actively make, between stereotypical signs of sustenance and indulgence, between sweet fruits of the earth and the strange delicacies of high culture. Unlike L’Aurore, Dial’s feminine figure does not exist in an idealist realm of beauty and truth but instead lives in the real world of race, gender, and class struggle. In an even larger sense, Dial’s representation of the position of woman in the world is also a repositioning of himself as a black person contemplating the life possibilities and “choices” at his disposal.

Improvising on what he saw in L’Aurore, Dial responded to the call of Bouguereau’s work in a way reminiscent of the African American dialogic practice known as “call and response.” For in Choices/Sunrise, Dial raps and riffs back and forth with the image and idea of L’Aurore, creating an ongoing dialogue that finally results in a work that is paradoxically related to Bouguereau’s image yet also expressive of Dial’s own personal and social concerns.

Drupal Theme and Development By: Cheeky Monkey Media

Site Design By: Constructive