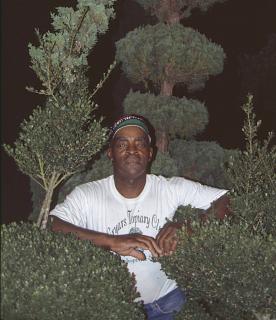

Pearl Fryar

About

Pearl Fryar was born in 1939 in the small town of Clinton, North Carolina. As he was growing up, he had no interest in trees or shrubs, or gardening of any sort. Even now he admits, "Plants are not so important to me; it’s what I do with them. Plants are just a means to do what I want to do." He is an artist like any other, talking about his medium.

His search for his place in the world took him first to New York. In 1975, after working ten years there with American National Can Company, he requested a transfer to their facility in Bishopville, South Carolina. When they refused, he quit his job and moved to Atlanta. "I stayed for exactly one year," he says, "and when American National realized I was serious about staying in the South, they got in touch with me and said if I’d come back to work with them they’d send me to Bishopville." That was September 1976.

In 1980 Fryar and his wife, Metra, bought their first piece of property. Theirs and the surrounding lands had once been a rural cotton field. They built a house, an attractive but conventional brick ranch, in an attractive but conventional middle-class neighborhood among African Americans with interests and aspirations similar to theirs. Fryar had originally budgeted for a garden, but home construction cost overruns ate up the allotted funds and put on hold the landscaping of the yard.

Fryar’s emerging creative impulses would not be put on hold. In 1982 he constructed a circular driveway and a walkway to his front door. He mixed and poured the concrete, into which he encrusted designs of stones, bricks, and pebbles. Presaging his later topiary work, the driveway’s rows of mosaics demonstrated a refined sense of balance and modulation rising out of complete improvisation, an apparent chaos belying skillful order. In describing the driveway, Fryar recalls that

I had seen mosaics before, like in books. Their looks stayed in my mind. When I decided to do that driveway. I realized I had a chance to do something different. I used cement and took flagstones, broke them up, pressed them in the wet cement. Marble chips, pebbles, rectangle-shaped cement blocks also got pressed in. My idea was to not repeat the same designs as I went around it. Like when I cut a row of trees, to make them similar but never identical. If you’re doing a series of abstract pieces you shouldn’t repeat them. Actually, you couldn’t repeat them if you wanted to.

Before he planted his first tree, Fryar had already demonstrated a talent comparable to those of recognized African American strip quilters and assemblage builders of the Deep South. But no one, not even Fryar, could have anticipated what was to come.

Fryar kept the yard around the house meticulously groomed, and when he heard that Bishopville had a Yard of the Month competition, he decided he wanted to win it. But when he learned that the contest was open only to town residents—he lived just beyond the city limits—he had to rethink his ambition.

"I told myself that I would just have to do something so they would make an exception, make it where they couldn’t help but change the rules." In 1985 he went to a Bishopville nursery, where a small sculpted plant caught his attention. The nursery’s owner encouraged Fryar to give topiary a try, and provided him with some preliminary instructions along with a malnourished juniper otherwise destined for the garbage. Fryar took home the shrub, planted it, nurtured it, pruned it, and became addicted. A holly bush came next, then another plant, and another—anything leftover or unwanted that the nursery gave him or sold him cheap. (More than a decade later, Fryar estimates that at least 25 percent of the plants in his yard were once somebody’s throwaways.) He gradually began to purchase the types of special plants that are seldom scrapped. He conceived and planted what he called a "frame"—rows of trees, shrubs and bushes—surrounding three sides of his yard. Over time the frame became an elaborate sampler of topiary possibilities, some of which are now between twelve and twenty feet tall.

As with most accomplished artists, Fryar possesses a healthy abundance of pride, confidence, and daring. An epigram he had seen while serving in the military stuck in his mind: He that does no more than the average will never rise above the average. "That quote was my inspiration," he explains. "All the plants I use are the ones you can usually find all over the gardens of South Carolina. So I wanted to go further. I started cutting shapes in a few plants. I liked what I was doing. After awhile I was cutting everything in the yard."

A personal philosophy developed. “I don’t want to copy what others have done, and I don’t want to do the same piece to work twice. My head is full of new ideas, and while I’m at work on a plant I’m already planning how it’s going to relate to the next one. Sometimes one piece over there“—he gestures to a section of his yard—”relates to some other one way on the other side of the yard. Sometimes it don’t. I love balance, you see. I put balance in every plant. I’m not talking about symmetrical kind of balance, I’m talking about balancing a combination of shapes, or a line and a curve.”

At one point a horticulturist friend gave him a topiary book from England, and Fryar endeavored to duplicate the accomplishments of his British counterparts. Having already acquired the necessary technical skills, Fryar successfully re-created some of die more challenging plants illustrated in the book, but he soon abandoned mimicry. "It wasn't me," he remembers. "I got my own way of doing it. The Europe stuff was too regular." When Fryar confronts a tree he clearly considers his pieces perennial works-in-progress, and prefers to keep things changing. He points out full-grown trees that have been undergoing regular makeovers for seven or eight years as they have grown up from saplings. He describes a particular Hollywood juniper as a "basic design" that somewhat resembles traditional topiary, yet is unmistakably Fryar's. "As it grows, I'm going to do more and more with it. It will become more abstract as it gets older and gives me more to work with."

Virtually all of his work is totally abstract, Fryar insists—with exceptions such as a tigerlike shrub and an abstracted juniper with two recognizable bulldog heads at the base. "I don't like to make animals and stuff like you see in topiary books. I just did those animals to show people I could do it. It just doesn't interest me."

Nevertheless, visitors divine all sorts of things in Fryar's work. "It's unbelievable what people will see in them," he muses. "I tell considers himself in command, not nature or another culture's or era's vision. He wants to create an unprecedented work every time. He says that

people come here to look at trees, things they know about, and then after a while they forget they're looking at plants.They get caught up in the art. They go away remembering that they looked at art. As long as you keep the flow of abstract shapes, you keep people's attention. Once you start repeating yourself, you're going to lose them. That's why students enjoy my yard. There's always movements, spirals, tiers, and abstractions that are never the same.

He avoids planning the shape of a piece in advance. He knows his ability to improvise will yield good results. As he works, ideas come to him. Frequently the finished topiary—that is, if any of Fryar's topiary is ever truly finished—is not at all what the artist anticipated at the outset. In his various roles as sculptor, gardener, and landscape architect, if he is especially satisfied with the form of a work he will maintain it essentially "as is," altering it slightly from time to time as he spots new possibilities. Most often, however, he considers his pieces perennial works-in-progress, and prefers to keep things changing. He points out full-grown trees that have been undergoing regular makeovers for seven or eight years as they have grown up from saplings. He describes a particular Hollywood juniper as a "basic design" that somewhat resembles traditional topiary, yet is unmistakably Fryar's. "As it grows, I'm going to do more and more with it. It will become more abstract as it gets older and gives me more to work with."

Virtually all of his work is totally abstract, Fryar insists—with exceptions such as a tigerlike shrub and an abstracted juniper with two recognizable bulldog heads at the base. "I don't like to make animals and stuff like you see in topiary books. I just did those animals to show people I could do it. It just doesn't interest me."

Nevertheless, visitors divine all sorts of things in Fryar's work. "It's unbelievable what people will see in them," he muses. "I tell them they are abstract, they represent form, imagination, that's it, but they say they can see real things there." Indeed, one observer has written, "From afar, Fryar's yard looks like the parapet of an enchanted castle. I saw green turrets and spires, spirals, loops, hearts, flags, fans and dozens of other shapes."

One might see a variety of inhabitants of an exotic menagerie in Pearl Fryar's Rorschach garden: a peacock here and a dragon there; a chi-lin, or a phoenix? A mermaid? A snail? A schmoo? They may or may not be there. Fryar is attempting to demonstrate the limitless possibilities of abstract form that he can coax from trees.

Still, abstraction need not mean limitation to empty or self-sufficient forms; Fryar's abstractions often contain buried subject matter. His comments echo explanations given by other twentieth-century African American vernacular artists:

I kind of camouflage my ideas. I'm sort of protecting myself. People see what they want to see, but I'm the only one knows what the pieces mean. A large number of pieces in my garden represent something special—a special person, or a place or a special event I walk through the yard and nobody except me knows what the pieces are, but they relate to things and bring back memories.

Some of the pieces I do symbolize someone I want to always remember. For example, when I grew up, black people could not show any emotion toward white people. White people I'd know from hanging around the tobacco barns, I couldn't show any friendship with. I wanted to be able to sit down and tell them they really made a difference, but I couldn't. Some of these people are in my work; they will never know it.

Pearl Fryar's garden independently carries forward millenniums of tradition. Topiary is said to have first been created in Rome two thousand years ago by a friend of Emperor Augustus. The art may have developed much earlier, for the instinct to shape and train trees and shrubs to beautify one's surroundings surely existed long before the Romans. Because topiary is, by its nature, relatively short-lived and requires continuous care, there are few examples today that are more than one or two centuries old. Even the extant versions of older traditional topiary gardens of Europe consist of what might be deemed "reproductions."

Topiary has appeared infrequently in areas where stone structures and sculptures are common. The popularity and widespread use of this art budded in those parts of England and Holland where stone masonry was expensive or rare and where suitable greenery was abundant. Early topiary simulated recognizable architectural shapes, such as columns, domes, spires, and occasionally, foreign exotica such as pyramids and obelisks. By the seventeenth or eighteenth centuries, the imagery of topiary became more representational, incorporating entertaining, ornate versions of such popular genre subjects as ships, hunters and their hounds, wild animals, birds, even trees (that is, trees designed to imitate other trees).

Eventually, by the late eighteenth century, European taste had drifted away from a fascination with formal elegance toward a preference for the natural-looking spontaneity of the jardin anglais, the English garden. Topiary survived, but mainly as backdrops and embellishment for baroque and neoclassical architecture, and as a readily available art form for certain ambitious gardeners. Save for eccentricities such as the elaborate topiary fantasies of Disney World, topiary gradually waned. And then along came Pearl Fryar.

Unlike the topiary artists of Europe, who usually learned from older practitioners and developed their craft within well-established conventions, Fryar seems to have reinvented the art completely on his own. Neither does he share a philosophy with African Americans such as Jesse Aaron, Bessie Harvey, and Ralph Griffin, all of whom worked with wood in its natural form and proclaimed that the material itself ordained the shape and subject of the finished work. Fryar is not even in concert with the creators of Japanese bonsai, who seek a sort of spiritual harmony with the tree and allow (or force) it to follow its own nature or replicate a natural landscape.

When Fryar discusses his work, he often reiterates that the trees and shrubs are not of great concern to him except as the medium of his art. He has learned the names of many of his favorite species, but admits that he has not bothered to commit all to memory. "I got a friend, he's a horticulturist, and he can tell you the official names for all of these," Fryar says. "I don't know a lot of them." Still, with no effort, he can identify almost two dozen: blue spruce, white pine, redtip photinia; Savannah, Foster, and yaupon hollies; dogwood and boxwood; Leyland cypress and weeping cypress; live oak, Hollywood juniper, nandina and pyrocantha. The array of growth patterns and textures in this variety gives Fryar the repertoire he needs to demonstrate his versatility. And he's still looking. "I shop around for something to try out. I love to experiment."

Fryar would prefer to talk process and technique rather than genus and phylum. His methods are as inventive as his sculptural forms. Spirals are created by winding twine around a thin tree; he camouflages the twine with a coating of black shoe polish. He employs wire coat hangers to produce spaces between branches. He loves to cut the foliage away from the trunks and branches, using the resulting bare wood as elements of color and design. Small branches, trimmed, spaced, and wired, are teased into the "fishbone" patterns that mark many of Fryar's most exciting creations. Remove all but two branches of a growing tree, bend them toward each other, tie the tips together, pointing them toward the ground, and a well-defined heart will develop. A particular juniper demonstrates. It begins as a basic three-tier topiary, but Fryar says, "I don't like to do anything you'd say you've seen before, so I had to put that heart on top to make it more original. I shaped that heart with a piece of wire. One of my techniques is to expose the branches, or the trunk of a tree. That's the art in it. You get different lines, different planes. You're letting the tree be exposed as a piece of art." He also uses PVC pipe to obtain even longer and more unusual shapes.

Fryar points out that he spends more time on his sculpture than on his full-time job at the American National Can Company, where he has now worked for over thirty years as a serviceman for the assembly line. He calls his place a "high-maintenance yard." He works each night, often until after midnight, sometimes much later when he is focused upon a foreseeable conclusion. His specially rigged lights bring near-daylight to a designated area. He constantly prunes, trims, edges, and shapes his plants, but only a fraction of an inch at a time. He makes his way through the property about once per month to ensure that each work gets regular personal attention. Much of his equipment is homemade. To reach the tops of the largest trees, he uses a ladder attached to a pickup truck. He prunes with a gasoline-powered trimmer that he devised to avoid using mobility-restricting electrical cords. Hand-held clippers add refinement to the works. But Fryar expends very little energy nurturing the plants: "I don't really stay on the new plants. I bring them home and I'll water them for a couple of weeks, and then let them go. After that, I don't water them or spray them with insecticide, and I never use fertilizer. I let nature control what happens. I use mulch, same as what nature gives plants in the forest."

In between his regular job and his irregular job, Fryar manages to spend a lot of time with high school students and underprivileged children. He brings them to his house for lectures and clinics, and uses topiary to explain the rudiments of geometry and chemistry to his young audience. There are other ways Fryar's yard is considerate of children. He has designed several small gardens around working fountains, because he loves "to see things that can hold children's interest." He also has devoted a corner of the yard to a collection of dozens of birdhouses, a veritable vacation resort for all types of resident and migratory birds. Although providing comfort for visiting birds is part of Fryar's motivation, he seems more satisfied with the pleasure his student guests derive from his cluster of birdhouses. A concrete statue of St. Francis of Assisi anchors the corner opposite the birdhouse complex. St. Francis stands amid the trees, preaching to, of course, concrete birds.

"My dream," Fryar says, "would be this: education. My heart is pretty much there. I want to see students from the bottom up be able to study my place and learn from it. Kids don't need to be interested in topiary. They can come here and learn to focus."

Hoping that he and his garden can be of maximum benefit to the town, Fryar has begun to plan new ways to interact with the community. A committee made up of local and state officials was recently established in Bishopville to create a team of student apprentices to assist and to learn from Fryar. The long-range goal of the program is to ensure the permanence of the garden and to encourage topiary throughout Bishopville and its environs.

Fryar's underlying motivation is ultimately to become a symbol of African American intelligence, talent, and success. A symbol, not a token.

I could have been a token fifty years ago. We need to open doors; don't need more tokens. Because of slavery, our people have always been thought of as laborers, not thinkers. My generation was the first to break that mold. I remember when I was a kid I wanted to be a math major and a jet pilot. My father said," You can't do none of that."You see, if I had gone to the military back then I would have been a mechanic. (I did go into the army later and was a chemical warfare specialist.)

My father was a sharecropper. We grew up on a farm. You had to make everything count, to take advantage of everything you had. My mother was a very good seamstress and made my sister's dresses out of hogs' printed feed sacks. My father used to make ax handles and baseball bats out of green hickory. He caned chair bottoms out of shucks. A lot of it was done out of need, out of necessity, for things we couldn't afford to buy. He'd sometimes sell the things he worked on, and we helped to save materials for him.

I was on a picket line in the early '60s up in Durham, North Carolina, and people was saying to me, "You better get out of there, man, you'll get yourself killed." And I said to them (and to myself), "If this is all I got to live for; I'll give my life to change it. I am not going back home to pick cotton."

If you've ever lived and been stereotyped, the hardest thing in the world is to break that stereotype. I set out to disprove the theory that black people can't think.

I started out to be a coin collector; and I was going to attract a lot of attention with a great coin collection. But when I started going to coin shows I realized that somebody with money could put together in one day what it took me five years, and I thought, This Is not it. Later on, trees gave me my opportunity.

We blacks are basically people who do not talk to our kids about things like business. Our kids always come out thinking about working for somebody else. I have white friends whose children say, "l want to go into Daddy's business," but black children can't do that.

The way to understand people is to study their culture. When I walk out there in my yard, and I do what I do, I'm showing what we can do, and what we always could do: a little thinking.

Quotations from Pearl Fryar are taken from four interviews conducted by William Arnett in 1997 and 1998.